On view through September 20, 2020

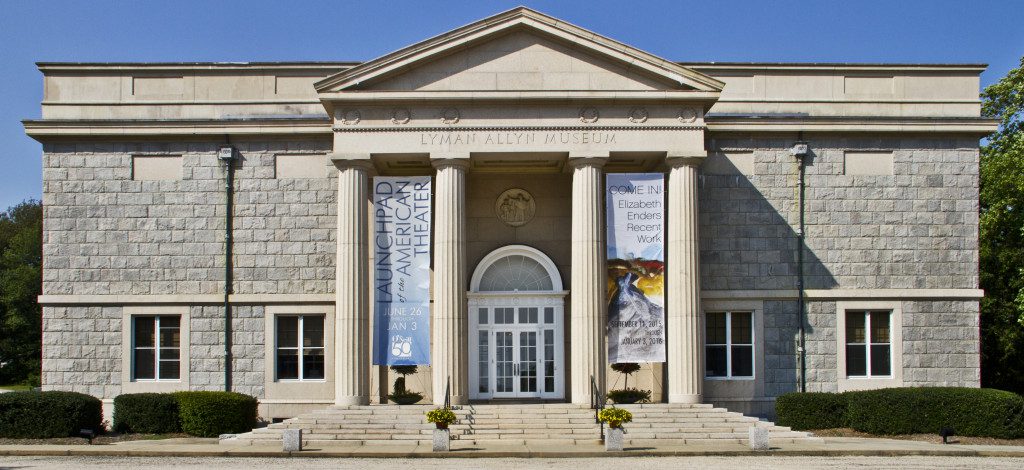

This exhibition showcases the Lyman Allyn’s collection of European paintings with a selection of portraits, history paintings, still lives, genre scenes, and landscapes from the early Renaissance through the 1800s. European paintings have been part of the collection since the Lyman Allyn opened in 1932, but the museum’s more recent emphasis on American art has placed its European paintings infrequently on view. Brought to Light reexamines the museum’s European paintings, sharing key pieces and their rich stories with the public.

The European collection is eclectic, the result of art acquired over decades through individual gifts and purchases. This installation, which occupies three adjacent galleries and the corridor, reflects consultations with subject specialists and recent research, with the goal of better understanding the collection and advancing scholarship.

Loosely organized by subject matter, Brought to Light presents a range of styles and topics by British, Dutch, Flemish, French, Italian, Spanish, and other European artists, suggesting both commonalities and differences in how painters in various eras and places approached their material, portraying people, places, and stories with enduring appeal.

Still Life and Genre Painting

Still life and genre paintings, or scenes of everyday life, emerged as categories of art in the Netherlands in the 17th century, although elements of both existed in earlier art and quickly appeared elsewhere. Expanding global trade brought wealth and urbanization to the Netherlands, creating new audiences for art and a demand for paintings concerned with these circumstances.

Still life paintings of flowers and ornate table scenes of food and luxury objects demonstrate an interest in beauty and material goods, intended to reflect the good taste and social status of art patrons. At the same time, these still life paintings caution against excess, suggesting in the temporary pleasure of flowers and food the fleeting nature of earthly possessions. In this era, women artists often specialized in painting still lifes, in part because their gender limited their access to studying and painting the human figure.

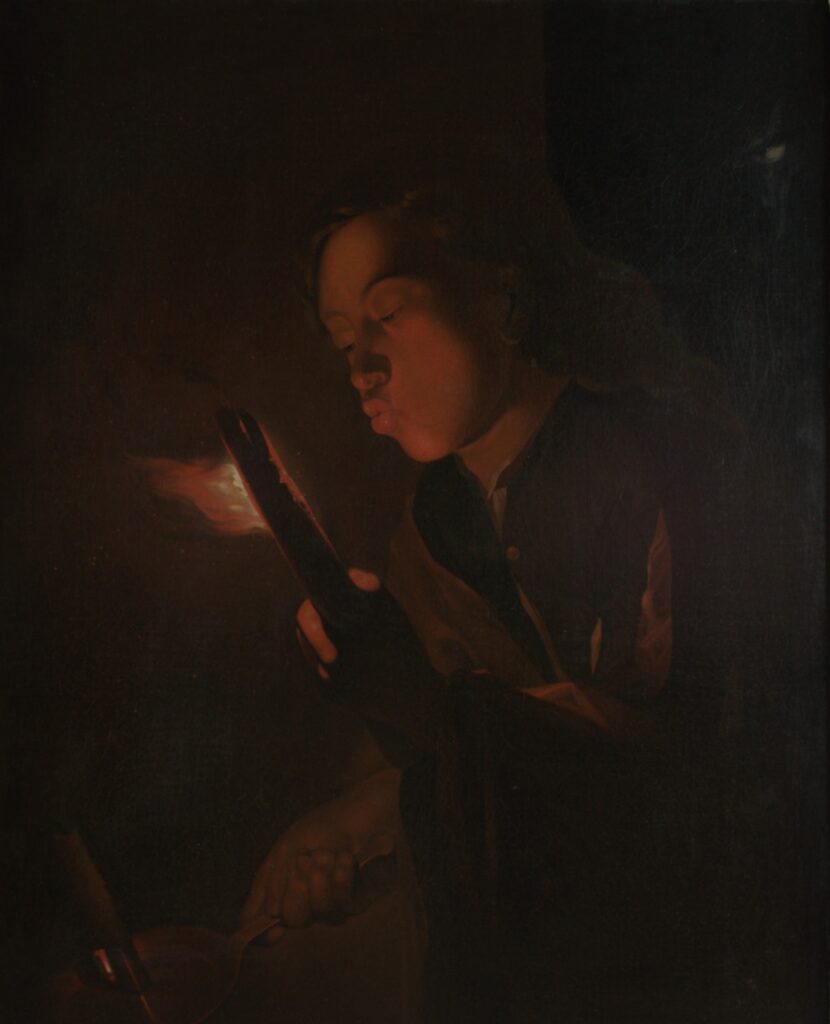

Genre paintings present scenes of everyday life, with a variety of subjects to interest viewers. These genre paintings feature a range of people—peasants, the nascent middle class, and the elite—generally involved in an activity, hinting at a larger story. Some scenes offer lessons in behavior, while others evoke a mood, suggesting love, friendship, or contemplation.

Although still lives and genre scenes were seen as less prestigious subjects for artists than history paintings, these painting types were extremely popular with patrons.

In a scene of lush abundance, fruit, flowers, shells, and shellfish are artfully strewn across a tabletop, offering a variety of textures and surfaces and evoking different smells and tastes. An imported Chinese porcelain bowl and an ornate goblet speak to the wealth and cosmopolitan status of the Dutch in the 1600s, an era known as the Dutch Golden Age.

In the 1600s, still life painting was less prevalent in Spain than in the Netherlands, but there were skilled Spanish artists producing scenes of flowers and fruit such as this one.

This artwork may have been painted by Juan van der Hamen y León (1596-1631), a talented and prolific still life painter working in Madrid in the 1620s, but more research is needed to substantiate this attribution.

This dramatically lit nighttime scene shows two young women reading a letter by candlelight. While the contents of the letter are unknown, it appears to be a love note written to the woman at left, who smiles in pleasure, while her friend glances up to gauge her reaction. The painting explores the nuances of light and mood, as a muted single light source suffuses the scene with a sense of mystery, camaraderie, and anticipated romance.

Paintings were a hugely popular commodity in the Netherlands in the 1600s, purchased by aristocrats as well as by merchants and workers to hang in their homes. Artists painted small scenes like this one on speculation for the art market rather than for a specific patron, carefully depicting everyday Dutch people and places, subjects with wide appeal.

Anthropomorphic landscapes similar to this one appear in German prints and in Netherlandish paintings in the late 1500s. Elements of this particular scene seem Flemish in style, yet much remains unknown about this fascinating painting.

While some Dutch and Flemish still life table scenes show a loose assortment of fruit, flowers, and luxury goods, this orderly composition illustrates the “banquet” still life type favored by some Haarlem artists such as Pieter Claesz, Willem Claesz, and Floris van Dyck. A decorative pastry meat pie forms the centerpiece, while expensive fruits, nuts, and other items arranged in bowls form a balanced composition. In the foreground, a roll on a metal plate rests just beyond the edge of the table, while a knife likewise extends into the viewer’s space, inviting us to imagine ourselves as participants in the feast.

In a critique of gluttony and excess, this wry feast scene is loosely modeled after the satirical print The Fat Kitchen, 1563 by Peter Bruegel the Elder. Despite the abundant food on view, the diners do not extend their hospitality to a thin, tattered beggar, who is being pushed out the door. At left a monk is drinking excessively instead of exhibiting temperate, religious behavior. The scene is descriptive as well as prescriptive, offering a sense of what furniture, clothing, and food preparation looked like in 1600 in the Netherlands and Flanders.

Bruegel’s Fat Kitchen was produced as one of a pair of prints, along with The Thin Kitchen, which shows starving peasants fighting for scraps. The extremes of feast and famine remind viewers that fortune can shift, suggesting moderation as the ideal path.

Honoré Daumier is primarily known for his satirical prints, which offered biting commentary on politics and social issues in the 1830s and ’40s, an era of upheaval in France. The dark, curving lines in this painting evoke the graphic look of Daumier’s lithographs, but unlike the critical tone of his cartoons, here there is only warmth and harmony. This scene may have been painted in the French Barbizon countryside on one of Daumier’s visits to see his friend and fellow painter Jean-François Millet, who painted peasants and rural life.

History Painting and Landscape

History painting, a term derived from the Latin term historia, meaning story or narrative, includes religious subjects from the Bible and scenes derived from Classical history and mythology. Religion, history, and literature were considered the most noble and prestigious subjects and French and Italian art academies placed history painting at the top of the hierarchy of genres established in the 1600s.

Religious paintings in this gallery depict saints and biblical episodes. Several early examples are fragments of altarpieces painted for devotional use in churches, while later paintings are studies for ceiling murals and religious canvases painted for individual patrons.

Greco-Roman history and mythology inspired the creation of an abundance of art beginning in the Italian Renaissance. Paintings here attest to the appeal of Classical figures such as Fortuna, the Roman goddess of fortune and luck, and the enduring fascination with Classical architecture. Artists and architects studied Roman ruins, painting iconic structures such as the Pantheon, and incorporating classical elements into landscapes. Landscape as a category of painting first emerged in the 1600s, but artists often integrated nature with other subjects. Pure landscapes gained popularity in the 1700s and 1800s.

This small, fragmentary panel of the Annunciation depicts the Angel Gabriel telling the Virgin Mary that she will bear the Son of God. Gabriel has just alighted outside the Virgin’s private chamber, interrupting her prayerful reading. Startled, she raises one hand to her chest, while God the Father in the upper left corner sends the Holy Spirit towards her.

Painted by the anonymous Spanish artist known as the Becerril Master in the early sixteenth century, this large panel was originally an independent devotional work or part of a retablo, a giant altarpiece that stood on the back of an altar or against the wall behind the altar. As was typical of many Spanish Renaissance paintings, the figure of Catherine appears rather flat in places because the artist and his patron were more interested in representing the deluxe, gilded features of the saint’s robe than in the credible depiction of three-dimensional space.

This tightly cropped representation of Saint Catherine of Siena (1347-1380) was once part of a larger painting featuring the dead Christ, part of whose left arm Catherine touches with her fingers. Executed by a Tuscan artist around the year 1500, the work reveals the painter’s sensitivity to design: note the individually delineated fingers and fingernails, the crisp contours of the facial features, and the sharp lines of the veil and religious habit. Catherine holds a lily in her right hand while she gazes pensively at Christ’s body. In the original composition, she would have been joined by other saints looking toward and perhaps touching Christ, thus guiding the viewer’s attention to his sacrifice for the salvation of humanity.

This composition is modeled after a print by the Italian artist Annibale Carracci, showing Jerome contemplating the Bible and a skull, reflecting on mortality and the sacrifice of Christ. The landscape in the background resembles Flemish examples, however, suggesting this scene was painted by a Flemish artist working in Italy.

Fortuna, the Roman Goddess of Fortune, floats gracefully through the heavens in this monumental painting, accompanied by a winged Amor, who tries to restrain her exuberance. As the personification of luck and fortune, she holds a purse aloft, dropping coins down onto the globe. Fortuna is generally shown carrying a cornucopia or a wheel in art, making this composition an unusual one.

Inspired by antiquity and the majesty of Rome’s classical ruins, Jan Frans van Bloemen painted idyllic scenes like this one. He combined ancient architecture from the Roman countryside (the campagna) with lush vegetation and imaginative elements. Here we see the Colosseum and other ancient structures in an idealized setting, bathed in a soft, warm light, while several figures in classical garb enliven the foreground.

Jan Frans Van Bloemen was among a group of Flemish artists painting in Rome that included his two brothers, Pieter and Norbert. Although his brothers returned to Flanders, Jan Frans never left, in part because he found considerable success painting for Roman aristocrats and for Grand Tourists, those who visited Rome as part of an educational circuit of culture and art in the 1700s and 1800s.

The Pantheon, a monumental domed temple built in the 2nd century under the Roman Emperor Hadrian, has endured intact as one of Rome’s most famous structures. It was as popular a tourist attraction in the 1700s as it is today, with visitors to Rome marveling at its brilliant engineering and the beauty of its design. At the center of the dome is an oculus that is open to the sky, providing an important light source.

Portraiture

A portrait captures and preserves an individual’s appearance, documenting it for family and posterity. Portraits reflect a negotiation between artist and sitter, with the sitter’s clothing, accessories, pose, and backdrop offering clues to their identity. Most portraits in this gallery depict specific individuals, probably rendered from life. They record the physical appearance of a person (or several people) and information about their economic status, values, and personality. For example, the books featured in several portraits suggest the sitters’ intelligence, literacy, and perhaps pious devotion.

European portraits from the Renaissance on tend to fit certain conventions, showing a sitter facing forward, turned in profile, or facing partway between front and profile. A sitter can be shown at bust-length, half-length, or full-length, with a larger size reflecting a greater cost to the sitter.

Before the invention of photography in the mid-1800s, paintings, drawings, and sculpture were the only means of documenting someone’s appearance. High child mortality and a shorter life expectancy meant that portraits had a memorial function, intended to record the appearance of a loved one and endure beyond a sitter’s lifetime.

In this charming double portrait of a richly dressed mother and child, a young girl stands on a table, placing her at almost the same height as her mother. The child holds a rattle attached on a chain to her waist and wears a necklace of coral beads, believed to have healing properties and to ward off disease.

An inscription on the upper right and left of this painting indicates that the infant was 19 months old in 1623 and the mother at right was 43 years old in 1625. This discrepancy in dates suggests the figures were painted at different times, perhaps marking a death.

The identity of this boy is unknown, but he was likely from a wealthy and noble family, as indicated by the full-length portrayal and the large scale of this portrait. The Stuart family had dogs that resemble this one, suggesting the possibility that this boy was a member of the royal family.

Britain’s King Charles II was restored to the monarchy in 1660 after a decade of instability under the rule of Oliver Cromwell. The restoration of the crown brought celebration and an embrace of aristocratic power. During his exile in France, Charles II came to appreciate refinement and fashion and he encouraged a new era of opulence in his court, inviting female courtiers in larger numbers than in his father’s reign. Elizabeth Wriothesley was one such figure in the Restoration court, and Peter Lely painted her several times, including this seated composition, which was reproduced as a mezzotint engraving. The small scale of this painting indicates that it is likely a secondary version of this portrait.

Elizabeth Wriothesley was a great beauty. The daughter of Thomas Wriothesley, Earl of Southhampton, she married Joceline Percy, Earl of Northumberland in 1662, and following his death, married Ralph, First Duke of Montagu, the English Ambassador in France.

With a simple gesture, a young woman shields her eyes from the sun, searching for her father returning with the day’s catch. She leans against an embankment, while her young brother rests on her shoulder. The siblings’ clothes are worn and patched, but their loving closeness, rosy cheeks, and beautiful surroundings make this scene a touching one.

This exhibition is generously supported by the Frank Loomis Palmer Fund, Bank of America, Trustee; and the Department of Economic and Community Development, Office of the Arts.